A new documentary examines the life of a SoundCloud star Tekashi 6ix9ine turned convicted criminal and a culture that makes us ‘all complicit’ in the rise of dangerous attention-seekers.

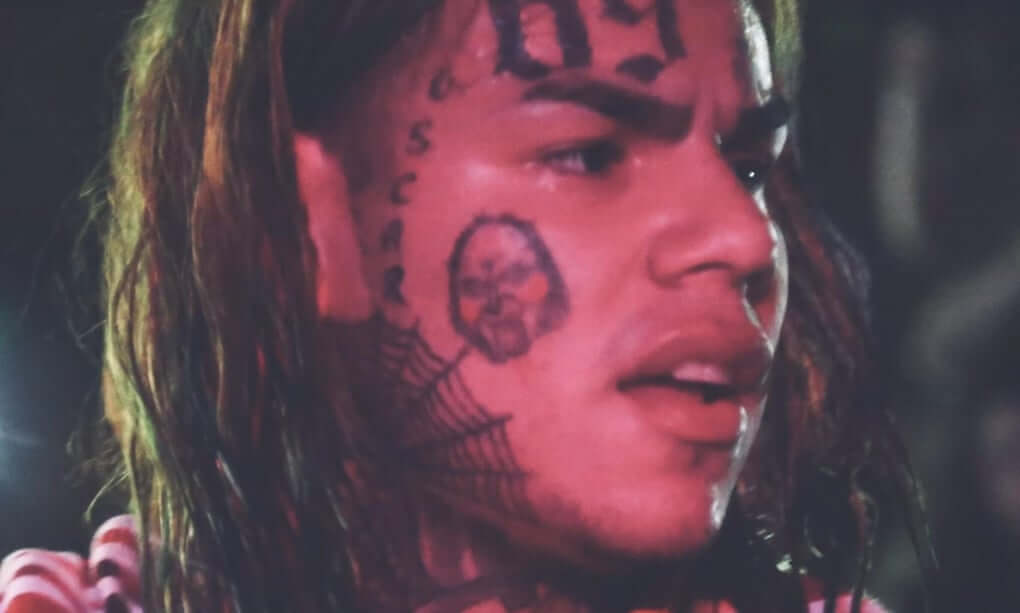

With his rainbow-colored tresses and prominent facial tattoos, it’s hard not to stare at SoundCloud rapper and viral sensation Tekashi 6ix9ine. The 24-year-old, who has collaborated with Nicki Minaj and Kanye West, wouldn’t have it any other way. More so than his actual music, the self-proclaimed social media “supervillain,” former gang member, and convicted felon is known for his shocking online antics and run-ins with the law. For him, no publicity is bad publicity – so does the latest Hulu documentary, 69: The Saga of Danny Hernandez, simply play into the young provocateur’s indiscriminate thirst for the spotlight?

Advertised as both an “investigative documentary” and a “gangster story,” the film traces the rapper’s life from childhood up to his arrest in late 2018 on charges that include attempted murder and armed robbery. A year earlier, he had embroiled himself with the Nine Trey Gangsta Bloods, a violent subset of the east coast prison gang, to bolster his image and street credibility. Gummo, his 2017 music video featuring cameos from several of the gang’s members, exploded in popularity. Things escalated quickly. He rode the coattails of associated infamy to break the internet before getting in too deep. Fast forward past multiple convictions and an abbreviated prison sentence due to his cooperation with the authorities, and today 6ix9ine has reached an all-time low as one of the most despised figures in hip hop.

“I was trying to find the moment where internet violence turned into real violence,” film-maker Vikram Gandhi tells the Guardian. “It’s one thing to have the symbols and look of violence with guns and gang affiliation. It’s about when the line is crossed into something else – physical violence, people getting punched in the face, groups going around shooting people – that’s when you know it’s not a show anymore.”

Fascinated by the new generation of SoundCloud rappers so divorced from his own conception of New York hip-hop, Gandhi discovered 6ix9ine in 2018 and picked up his camera around the time of his arrest months later. Somewhat of a prankster himself, Gandhi knows a thing or two about posturing for attention. In Kumaré, his 2011 documentary, he posed as a spiritual guru and gained a number of followers despite being a fake. In 69, he drops the costume and plunges into the life and times of the notorious figure whose invented persona became too real for his own good.

Before his rise, 6ix9ine was Danny Hernandez, a first-generation New Yorker born to immigrant parents from Mexico and Puerto Rico. Raised in poverty by a single mother and traumatized by his father’s absence and his stepfather’s murder, Hernandez led a difficult childhood in the shadows of anonymity before discovering the powers of Instagram and YouTube. “When I realized he grew up in Bushwick, close to where I live,” Gandhi tells the Guardian in a video call. “I realized I knew exactly the neighborhood he was from and the bodega he worked in.”

Drawing from past interviews, social media posts, audio recordings, videos, court documents, and transcripts, Gandhi summons the digital spirit of Tekashi 6ix9ine without ever actually speaking to him. The rapper’s team ignored Gandhi’s interview requests and has recently denounced the documentary. But for the film-maker, 6ix9ine’s cooperation never really mattered. “When I started I didn’t know if he was going to get out of prison. He could have been sentenced for much longer. I was making the film whether he came out or not,” Gandhi explains. “In long-form film-making, you will always have a narrative arc that’s beyond some people’s control. I think [6ix9ine] is inclined to do interviews where he can manipulate the narrative. He lives so much of his life online, anyway. That’s where he really exists. What would he tell me that he hasn’t already said?”

Indeed, Tekashi is skilled at absorbing bad press and turning it into something positive, knowing that attention is the currency of fame. From his early days designing clothes featuring profanities drawn in big, bold letters, to his button-pushing music videos and high-profile social media beefs, he knows that provocation will rack up the “likes.” In fact, his persona relies on constantly one-upping himself in a never-ending game of dare. In his first music video out of prison, Gooba, he depicts himself as a rat, at once acknowledging his new reputation as a snitch, and shrugging off its importance. The film draws a timeline of his various sentences and controversies, yet no matter the scandal he bounces back, revealing a cold, casual attitude towards his accusers, and those he’s betrayed or harmed.

“None of the information we share is new. But with [the film] we give a human face to a lot of people who in the past have just been depicted as pawns in [6ix9ine’s] story,” Gandhi says. He interviews neighbors and former friends that knew Hernandez before he was throwing gang signs at the camera. But the most poignant of Gandhi’s subjects is Sara Molina, the former girlfriend, and mother of Hernandez’s daughter. Molina paints a damning portrait of her ex-beau as a physically abusive partner and indifferent father too addicted to fame to care about anyone but himself. “For everyone in the movie, [6ix9ine] is a triggering person. Almost everybody that I interviewed that was close to him struggled. It was like they were all talking about a good friend that screwed them over.”

A cautionary tale about the destructive powers of fame-seeking in the age of social media, Tekashi’s story might recall that of another American villain skilled in media manipulation. “Dave Chappelle once said after [Donald] Trump was elected that we elected an internet troll as our president. I don’t think that anyone could imagine at the time that the attention that was being given to him might actually make him win.” Gandhi says. “[With Tekashi 6ix9ine], the hip hop world and the internet created a troll and gave him fame and fortune. We’re all complicit in this attention giving economy.”

When asked about the objection some have towards amplifying people who have proven themselves undeserving of the spotlight, Gandhi shrugs: “I don’t have an answer on whether the film is good or bad for society, or good or bad for [6ix9ine’s] career. The only thing I can do is take a subject that is taboo and open it up. I think we have to address things instead of canceling them. Why did this thing happen? If you were someone who was obsessed with the story, or someone who regrets being a fan of his, you can look at the film and say, ‘This is what went down’.”